Many Americans will celebrate Martin Luther King Day this month. Much has changed since King proclaimed his dream at the Lincoln Memorial in 1963, but the resonance of a true celebration is in its contemporary relevance. So, in a society that witnessed the passage of fundamental civil rights laws in the mid-1960s, what may we celebrate?

The overt discrimination of racially segregated bathrooms and the refusal of service at lunch counters have disappeared. Educational opportunities for black students have been extended. The cadre of black professionals has grown. Job opportunities have improved.

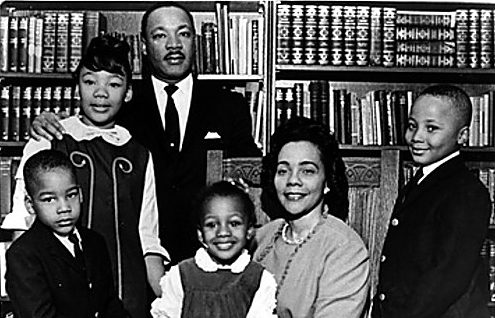

Yet forty-nine years after his assassination, the most enduring meaning of his life, especially in our divided country, arises out of his stirring words, “I have a dream.” For King, that memorable speech was grounded in a very personal longing. King’s dream envisioned a day when his four little children would live in a nation where they would be judged “not by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.” He said, and rightly so, that his dream was “deeply rooted in the American dream,” the uniquely American vision of a society in which every life will be lived in freedom–equal freedom–under law.

That freedom is ultimately the freedom to aspire. Our understanding of what is good in life is not monolithic. Some dreams are widely shared, and some are highly individual. The American dream does not prescribe the specifics of how we should aspire. Instead, it envisions a society in which every citizen will have opportunities to learn and develop skills to pursue a life that matters to that individual. The dream is that American society will support people who, in the process of pursuing their own dreams, naturally seek out others to create partnerships that generate benefits not only for them but also for others who share their aspirations.

In my own way, I have been a beneficiary of the American dream. I have learned skills important to me. I have found employment sharing those skills and their fruits with others. I have had the opportunity to pursue ideas that matter deeply to me, including the ideas that are developed in Cooperative Wisdom. I have played a part in many, many cooperative projects that have helped me convert my aspirations into genuine benefits for the people and communities I care about.

But, like everybody else, I am an individual. my taste in food, clothing, entertainment and even philosophy is in many ways unique to me. The people who care about me know my preferences. My wife picks her moments for key conversations with me. My grandchildren know grandpa will make any experience an occasion for teaching a lesson.

In turn, I treasure them as individuals. I may not be a big fan of Thai food, but I’ll take a grandchild to a Thai restaurant because it delights her. I regularly make a commitment to light opera because my wife’s enjoyment has led me to enjoying it with her. Even these family relationships make it clear that “Do unto others as you would have others do unto you,” does not tell me to play for them the music I like or prepare for them the food I prefer. Instead it asks me to appreciate them as individuals who, like me, have a unique combination of experiences, insights, capabilities and aspirations.

This is at the core of King’s dream: the political liberty we cherish will support every girl and boy, every woman and man, as they pursue their own aspirations. In the process, all of us will seek out others who share those aspirations and work with them to create communities that generate benefits because they affirm and honor diverse dreams.

This mutual respect for aspirations is the foundation of Cooperative Wisdom. We wrote at length about Dr. King in the book because he embodied so many of the social virtues we espouse. A day in his honor is an opportunity to renew our respect for King’s dream, our dedication to the American experiment and our pledge to liberty and justice for all.

Leave a Reply