Americans are having a lot of trouble agreeing on what is true. This isn’t surprising to philosophers. For centuries, they’ve been debating how we know what we know and what counts as acceptable forms of verification.

Recently, however, “Alternate Facts,” “Inconvenient Truths” and “Fake News” have all become part of a divisive political rhetoric. As authors of Cooperative Wisdom, we have no interest in using these buzzwords to disparage others. Our nation needs more cooperation and community, not intensified conflict.

There’s no question that creating a sense of community is easiest when people share experiences they have in common. But we also know that community is often most rewarding—and most sustainable– when it grows out diverse viewpoints that reflect different experiences. In the face of conflicts that threaten to divide or even destroy us, we need to manage our fears and biases. Only then can we take in information that may be outside our own experience. Instead of ignoring information we do not understand, we need to evaluate it.

Most people start with a common sense approach to fact. We trust what we can verify for ourselves. We know fire is hot. We can confirm that a child is two years old. We can say, with confidence, that someone has a fever if the thermometer registers 101.

Better Facts = Better Decisions

Knowing what is true matters because we make better decisions if we have the facts. Once we understand that fire is hot, we don’t stick our hand into a flame. When we know a child is two, we don’t expect her to be able to read. If we can verify that someone has a fever, we can give them appropriate medications.

Because decisions based on facts are better, we are right to be concerned about misinformation. When someone provides information that doesn’t align with our understanding, it makes sense to be skeptical. If it seems they are ignorant or misinformed, we may actually feel a responsibility to provide more accurate or up-to-date information. If a diabetic friend orders soda at lunch, we’ll want to be sure he or she has relevant facts about how soda might elevate blood sugar and the complications that might cause.

Sometimes, of course, people deliberately use misinformation to get us to make decisions that aren’t in our best interest. A store might make false claims about merchandise. A pharmaceutical company might be deceptive about the results from clinical trials. A candidate might promise something he or she doesn’t intend to deliver. In those cases, we are right to be wary and even angry. That’s why fake news, alternative facts and inconvenient truths strike a nerve. Each term suggests manipulation—someone trying to obscure, conceal or distort the truth to put us at a disadvantage. Each term reveals a vulnerability that deserves deeper consideration.

Fake News

For many things that really matter in our complex contemporary society, the facts cannot be ascertained by individuals. A person may be able to say with confidence that it is raining, but he’ll need an expert to report on how much rain has fallen in the past year and how that compares to previous years and other locations. An individual may know that the price of phone service has increased, but she’ll need an economist to explain the market forces that made that happen.

Scientists and journalists are, in their best incarnation, experts who try to determine the truth of the matter. Both have a professional commitment to digging out and reporting facts. When they are properly trained, they follow the evidence regardless of where it takes them. They learn to recognize and compensate for their own biases. And they offer the rest of us insight beyond our own experience, using their tools and expertise, to uncover facts that we wouldn’t otherwise understand.

Fake news and, for that matter fake science, is an effort to exploit the trust we have traditionally placed in science and journalism. The Internet has made it easier for people to replicate the appearance of authority. Anyone can come up with a plausible name and start posting things in the hope that the gullible will be misled. The fact that some information is manufactured doesn’t change the need for expertise.Instead, it puts a burden on the rest of us to be more discerning in identifying legitimate experts who are making a bona fide effort to provide us with the best available facts about things we can’t observe for ourselves.

Inconvenient Truths

This phrase reminds us that we can’t do just one thing. Every action has a multitude of effects, and some will surprise us. For instance, everything we eat comes from somewhere. Where it was grown, how it was harvested, the procedures for processing—all have consequences. Some are beneficial—we have food on our tables—but there are often harms hidden among the benefits. Some harms may be conspicuous—an outbreak of salmonella for example–but others will be miniscule. They would be insignificant, but they occur in the context of mass markets.

With thousands of repetitions, effects accumulate. As an example, consider food waste. When one family cleans out the fridge and tosses a few items that have expired or gotten moldy, it doesn’t seem like a big deal. But experts now estimate that over 40% of food is discarded, creating methane issues in landfills. Having someone point out these problems of scale can definitely be irksome. What we are doing seems insignificant from our point of view, but we need to expand our vision to understand harms that may be accumulating.

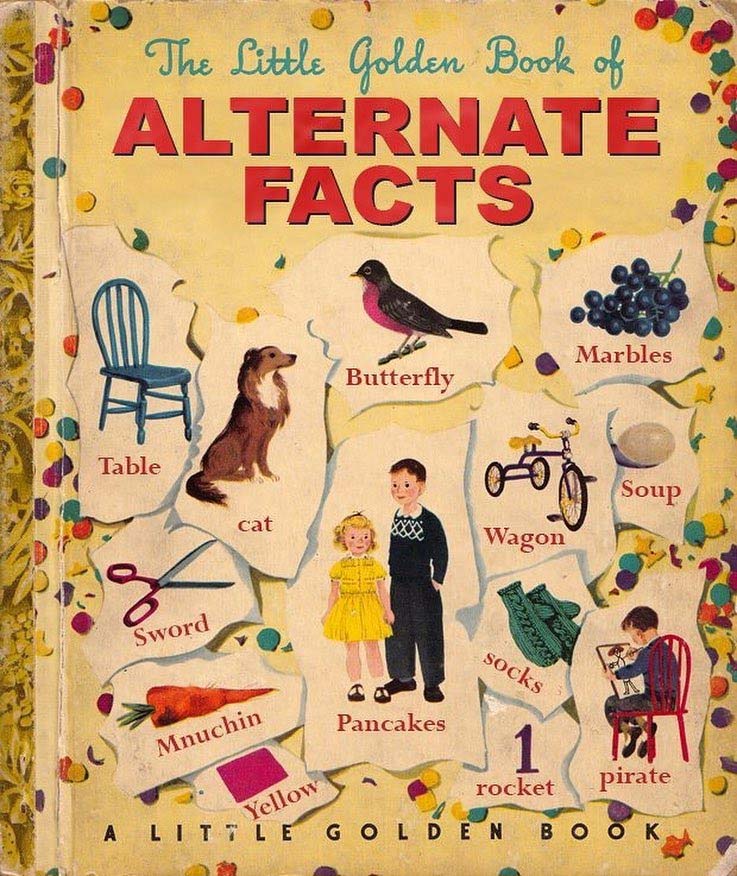

Alternate Facts

Alternate Facts can, of course, be a rhetorical trick, an effort to turn a lie into something more acceptable. But the term also alludes to the important matter of perspective. Each of us is situated slightly differently so we see reality from a different vantage point. What is an obvious fact for one person may not be so obvious to someone else. As a simple example, my co-author, Dr. Scherer lives in Northwest Ohio. If he tells me it is snowing, I might (foolishly!) dispute his statement. I live on the Central Coast of California, and it isn’t snowing here!

The same legitimate variation in perceived facts applies to larger issues of policy. Many people agree, for example, that energy independence is a legitimate goal for the United States. People disagree about how to achieve that goal in part because they have different perspectives based on where they live, what industries they are involved with and what resources they understand. This is clearly a case in which there is not a single solution. Many means can be employed to meet the broad goal of energy independence, and our policies will be most sustainable if we keep up with emerging facts that are clear from different perspectives. New blade designs, for example, may make wind turbines more efficient or thin film technology may make solar power more competitive.

Beyond Buzzwords

Catchy slogans like Fake News, Inconvenient Truths and Alternate Facts encourage us to be dismissive of anything that doesn’t correspond to our own understanding of the facts. It’s easy to categorize news as fake when it doesn’t align with our preconceptions. It’s tempting to dismiss inconvenient truths that in our experience are small and insignificant, especially if we don’t see their accumulation. It’s appealing to mock alternate facts rather than trying to understand whether an alternative perspective reveals something we can’t see from where we are standing.

Unfortunately, the rhetoric of fake news, inconvenient truths and alternate facts obscures a more serious matter. We need the best information we can get in order to make good decisions and wise policy. The fundamental strength of a society lies in its freedom and will to gather, scrutinize and evaluate information. To do this, we have to depend on reliable experts, be open-minded about facts that don’t fit our preconceptions and appreciate the contributions of alternate viewpoints.

Our understanding of what is true evolves as our environments change. None of us can keep up, so we must depend on each other. Cooperative Wisdom requires open and respectful discussion of what we regard as facts. What evidence supports or challenges them? We need to be discerning about our own biases, compassionate about confronting previously ignored harms, and courageous in challenging those who would mislead us in order to gain an advantage. If we practice those virtues, we are more likely to establish the kind of durable facts which can inform good decisions and create a sustainable sense of community.

Leave a Reply